Pregnancy is the progression and sequence of transformations occurring in a woman’s organs and tissues due to the development of a fetus. The complete journey and Symptoms of Pregnancy, from fertilization to childbirth, typically span an average of 266–270 days, roughly equivalent to nine months. (For pregnancies in species other than humans, refer to gestation.)

The normal events of pregnancy

A novel individual is formed when the components of a potent sperm combine with those of a fertile ovum, or egg. Before this union, both the spermatozoon (sperm) and the ovum undergo extensive migration to facilitate their meeting. Numerous actively motile spermatozoa are introduced into the vagina, traverse the uterus, and penetrate the uterine (fallopian) tube, surrounding the ovum. The ovum, having been released from its follicle or capsule in the ovary, reaches the tube. Upon entering the tube, the ovum sheds its outer layer of cells due to the action of substances in the spermatozoa and the tubal wall lining. This loss allows multiple spermatozoa to breach the egg’s surface, although typically only one becomes the fertilizing organism.

After entering the ovum, the nuclear head of the spermatozoon detaches from its tail, with the tail gradually disappearing. The head, containing the nucleus, enlarges as it moves toward the ovum’s nucleus, referred to at this stage as the female pronucleus. The head transforms into the male pronucleus, and the two pronuclei converge in the ovum’s center, where their threadlike chromatin material organizes into chromosomes. Initially, the female nucleus possesses 44 autosomes (non-sex chromosomes) and two (X, X) sex chromosomes. Before fertilization, a reduction division reduces the number of chromosomes in the female pronucleus to 23, including one X chromosome. The male gamete, or sex cell, also has 44 autosomes and two (X, Y) sex chromosomes, but a reducing division before fertilization leaves it with 23 chromosomes, including either an X or a Y sex chromosome at the time of merging with the female pronucleus.

Following the merging of chromosomes and mitotic division, the fertilized ovum, now called a zygote, divides into two equal-sized daughter cells. Each daughter cell inherits 44 autosomes, half maternal and half paternal, along with either two X chromosomes (resulting in a female) or an X and a Y chromosome (resulting in a male). The sex of the offspring is determined by the male parent’s sex chromosome.

Fertilization occurs in the uterine tube, and although the duration of zygote residence in the tube is uncertain, it likely reaches the uterine cavity about 72 hours post-fertilization. Nourished by secretions from the tube’s mucous membrane during its journey, the zygote transforms into a solid, mulberry-like mass known as a morula by the time it reaches the uterus, composed of 60 or more cells. As the cell count increases, the zygote assumes a hollow, bubble-like structure called a blastocyst. Floating freely in the uterine cavity and sustained by uterine secretions for a brief period, the blastocyst eventually implants itself in the uterine lining, typically in the upper portion. (The implantation process is described below.)

Diagnosis of pregnancy

Early outward indications of pregnancy encompass missed menstrual periods, morning nausea, and breast fullness and tenderness. The definitive signs of gestation include the audible sounds of the fetal heartbeat, detectable with a stethoscope between the 16th and 20th week of pregnancy, ultrasound images of the developing fetus observable throughout pregnancy, and fetal movements typically commencing by the 18th to 20th week.

For individuals tracking their body temperature upon waking, continued elevation beyond the missed period is strongly indicative of pregnancy. During the initial months, women may experience frequent urination due to pressure on the bladder from the enlarging uterus, fatigue, aversion to once-liked foods, a sense of pelvic heaviness, and, at times, vomiting and pulling pains in the abdomen as the growing uterus stretches round ligaments. Most of these symptoms subside as pregnancy progresses, and by the 12th week, the signs and symptoms become distinct enough to facilitate diagnosis.

Biological pregnancy tests rely on the production of chorionic gonadotropin by the placenta, with an accuracy of about 95 percent. However, false-negative tests, possibly up to 20 percent in a series of cases, may occur, particularly in late pregnancy when chorionic gonadotropin secretion decreases. False-positive results are also possible, making the tests probable rather than absolute evidence of pregnancy. Chorionic gonadotropin presence only indicates the presence of living placental tissue and provides no information about the fetus’s condition.

Immature mice (Aschheim-Zondek test) and rats provide highly accurate results in testing, whereas more rapid and cost-effective frog and toad tests have largely replaced tests involving rabbits (Friedman test).

Immunological reaction tests based on the inhibition of hemagglutination are commonly used. Positive results occur when human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) in the woman’s urine or blood inhibits the combination of coated particles and HCG antiserum. The absence of chorionic gonadotropin leads to agglutination, resulting in a negative test.

Physician-noted signs suggestive of early pregnancy include darkening of the areola, prominence of Montgomery’s glands around the nipple, purplish-red discoloration of vulvar, vaginal, and cervical tissues, softening of the cervix and lower part of the uterus, and enlargement and softening of the uterus itself. While these signs are suggestive, they are not necessarily conclusive proof of pregnancy.

Conditions that may be mistaken for pregnancy

Several conditions can complicate the diagnosis of pregnancy. The absence of menstruation may be attributed to chronic illness, emotional or endocrine disturbances, the fear of pregnancy, or a desire to become pregnant. Nausea and vomiting may have origins in gastrointestinal issues or psychological factors, and breast tenderness can result from hormonal imbalances.

Pelvic congestion, such as that caused by a pelvic tumor, can lead to duskiness of genital tissues. Occasionally, a soft uterine tumor may mimic pregnancy symptoms. If a woman experiences irregular menstruation without other signs of gestation, it suggests she is not pregnant. Some rare ovarian and uterine tumors can produce false-positive pregnancy test results. When the uterus is challenging to feel due to a backward tilt or enlargement from a tumor, pregnancy exclusion may be challenging for the physician. However, if other pregnancy signs are absent and pregnancy tests are negative, the likelihood of pregnancy is minimal.

Childless women with a strong desire for a baby may suffer from false or spurious pregnancy (pseudocyesis). They may cease menstruating, experience morning nausea, claim to “feel life,” and have abdominal enlargement due to fat and intestinal gas. At the supposed term, they might even report “labor pains,” despite the absence of typical pregnancy signs. Treatment for this condition involves psychotherapy.

Menopausal women, fearing pregnancy when their periods cease, are often reassured by the absence of pregnancy signs. Retained uterine secretions, consisting of bloody or watery fluid trapped above a blocked cervix, can impede menstruation, soften, and enlarge the uterus, leading the patient to question whether she is pregnant. However, the absence of other pregnancy signs and a closed cervix, obstructed by scar tissue, clarifies the situation.

Duration of pregnancy

Typically, there are 266 to 270 days between ovulation and childbirth, with variations ranging from 250 to 285 days. Physicians commonly determine the estimated delivery date by adding seven days to the first day of the last menstrual period and counting forward nine calendar months. For instance, if the last period started on January 10, the calculated delivery date is October 17. In legal contexts, courts may acknowledge shorter or longer gestation periods as potentially legitimate. Some courts, such as one in New York, have accepted a pregnancy duration of 355 days as legitimate, while British courts have recognized 331 and 346 days with medical approval. Fully developed infants have been born as early as 221 days after the mother’s last menstrual period.

Due to the uncertainty surrounding the exact date of ovulation, accurately estimating the delivery date is often challenging. There is a 5 percent chance that a baby will be born on the estimated date derived from the mentioned rule. A 25 percent chance exists for birth within four days before or after the estimated date, a 50 percent chance for delivery within seven days of the estimated date, and a 95 percent chance for birth within 14 days before or after the estimated date of delivery.

Anatomic and physiologic changes of normal pregnancy

Ovaries

The ovaries of a nonpregnant, healthy young woman undergo cyclic changes each month, revolving around a follicle or “egg sac.” Following each menstrual period, a new follicle emerges, releases an egg through ovulation, and subsequently transforms into a structure known as the corpus luteum.

In the event of fertilization, the hormones produced by the corpus luteum sustain the fertilized egg briefly. Progesterone and estrogen, secreted by the corpus luteum, play a crucial role in preserving the pregnancy during its early stages. If pregnancy doesn’t occur, the egg disintegrates, and the corpus luteum diminishes. As it shrinks, the stimulating impact of its hormones on the endometrium (the uterus lining) wanes, leading to menstruation. The cycle then repeats.

During pregnancy, the developing placenta maintains the corpus luteum through its hormones, rendering the corpus luteum non-essential after the initial weeks. Human pregnancies have continued successfully even after the removal of the corpus luteum as early as the 41st day after conception. Over time, the placenta begins producing progesterone and estrogen independently, and by the 70th day of pregnancy, it fully takes over the functions of the corpus luteum without jeopardizing the pregnancy. Towards the end of pregnancy, the corpus luteum typically regresses and becomes less prominent in the ovary.

In the initial months of pregnancy, the ovary housing the active corpus luteum is notably larger than the other ovary. Both ovaries often develop fluid-filled egg sacs due to chorionic gonadotropin stimulation, but most of these follicles gradually regress and disappear by the end of pregnancy.

Pregnancy results in an increased blood supply to both ovaries. Both glands commonly display patches of bright red fleshy material on their surfaces, indicative of a decidual reaction when examined under a microscope. This reaction involves the development of cells resembling those in the lining of the pregnant uterus, influenced by the elevated hormone levels during pregnancy, and these cells vanish after the pregnancy concludes.

The uterus and the development of the placenta

The uterus is a pear-shaped organ, approximately 7 centimeters (about 2.75 inches) long and weighing 30 grams (about one ounce) in a nonpregnant woman in her late teens. It features a button-like lower end, the cervix, merging with the bulbous larger portion called the corpus, which constitutes about three-fourths of the uterus. The uterus has a flat, triangular-shaped cavity. During pregnancy, the uterus transforms into a large, thin-walled, hollow, elastic, fluid-filled cylinder, measuring around 30 centimeters (about 12 inches) in length, weighing about 1,200 grams (2.6 pounds), and having a capacity of 4,000 to 5,000 milliliters (4.2 to 5.3 quarts).

The increased size during pregnancy results from a significant rise in muscle fibers, blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels in the uterine wall. Additionally, there is a five- to tenfold increase in the size of individual muscle fibers and notable enlargement of blood and lymph vessels.

In the initial weeks of pregnancy, the uterus maintains its shape but becomes gradually softer, forming a flattened or oblate spheroid by the 14th week. The cervix softens and develops a protective mucus plug. The isthmus, the lower part of the corpus, elongates and transforms into the lower uterine segment, a bowl-shaped formation, as the uterine contents require more space. The fibrous nature of the cervix resists this unfolding action.

The uterine wall undergoes stretching and thinning during pregnancy due to the growing conceptus (the entire product of conception) and the surrounding fluid. By term, this process turns the uterus into an elastic, fluid-filled cylinder. The cervix gradually thins and softens late in pregnancy, eventually dilating during labor for the passage of the infant.

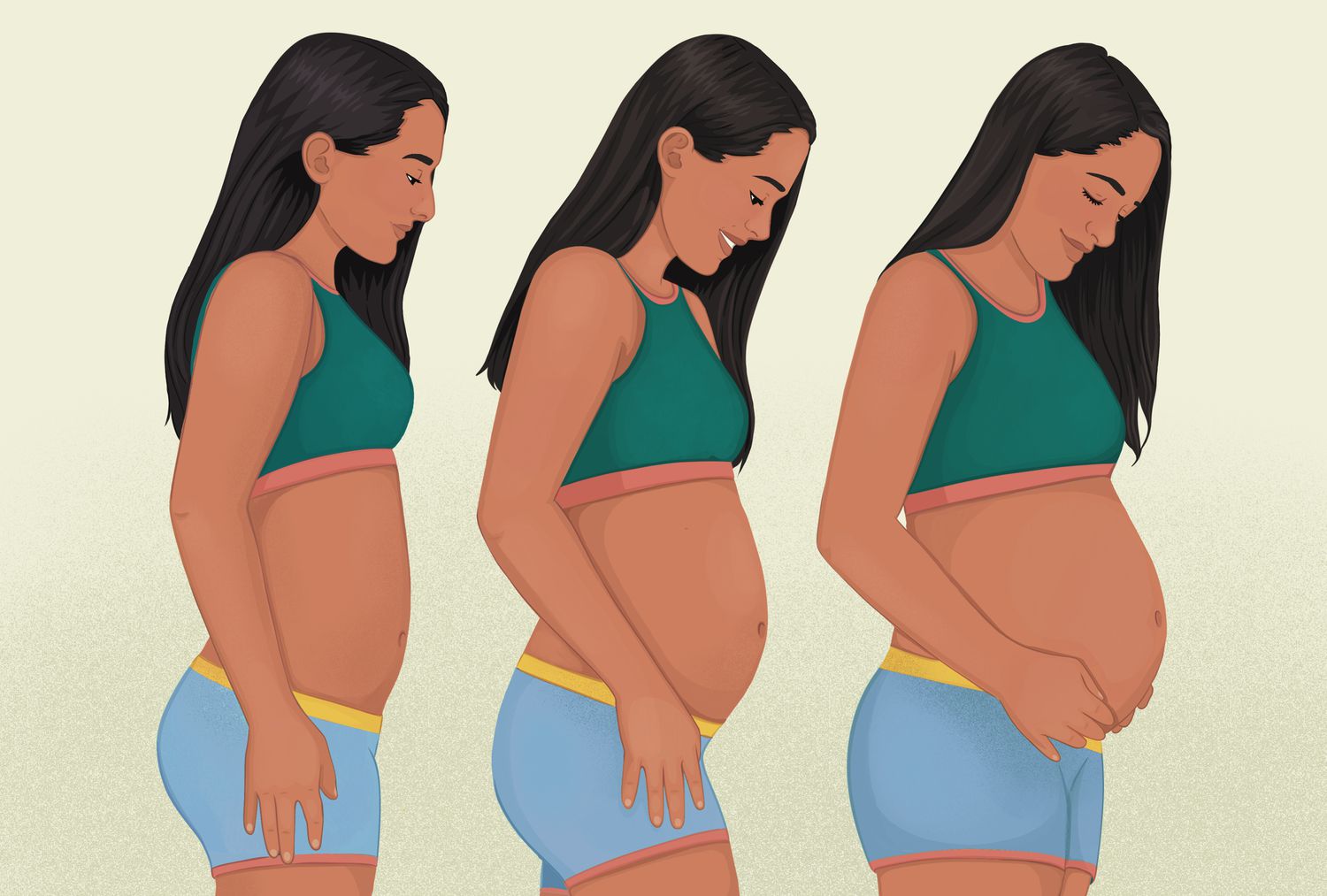

As pregnancy progresses, the uterus rises out of the pelvis, filling the abdominal cavity. Near term, it becomes top-heavy, falling forward and rotating to the right due to the large bowel on the left side. This position exerts pressure on the diaphragm and displaces other organs. Lightening or dropping may occur several weeks before term as the fetal head descends into the pelvis. However, in some women, particularly those who have borne children, lightening may not occur until the onset of labor and may be impossible in cases of an abnormally small pelvis, an oversized fetus, or a fetus in an abnormal position.

After fertilization, the conceptus, a minute bubble-like structure called a blastocyst, initially floats unattached in the uterine cavity. The trophoblast, a special layer of cells with the ability to attach and invade the uterine wall, surrounds the blastocyst. The conceptus contacts the uterine lining about the fifth or sixth day after conception, forming a rounded disk with the embryonic mass on the surface. The trophoblast, in contact with the endometrium, invades maternal tissue as the blastocyst collapses, sinking into the uterine lining.

The blastocyst becomes buried in the endometrium, and the proliferation of the trophoblast covers the blastocyst. A cavity forms, becoming the fluid-filled chorionic cavity containing the embryo. This cavity ultimately houses the amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus, the fetus itself, and the umbilical cord.

The body stalk, destined to become the umbilical cord, separates the embryo from the syncytiotrophoblast, the outer trophoblast layer against the endometrium. Maternal blood enters the blood mass through uterine arteries, and erosion of the endometrium allows connection with small cavities in the trophoblast. The placenta develops, and fingers of proliferating cytotrophoblast cells extend into the syncytiotrophoblast. By the third week of Symptoms of Pregnancy, the syncytiotrophoblast covers growing villi, forming a layer within the blood-filled spaces.

Chorionic villi on the outer surface of the chorionic sac, covered by cytotrophoblast, develop embryonic blood vessels. By the fifth month, the cytotrophoblast begins to regress, disappearing. The decidua basalis, a thin plate of cells formed from the endometrium closest to the conceptus, constitutes the maternal component of the mature placenta. The chorionic villi and their blood vessels, forming the fetal part, are separated from the decidua basalis by fluid blood. The chorionic cavity contains the fluid in which the embryo floats.

At term, the normal placenta is a disk-shaped structure, approximately 16 to 20 centimeters (about six to seven inches) in diameter, three to four centimeters (about 1.2–1.6 inches) thick at its thickest part, and weighing between 500 and 1,000 grams (1.1 and 2.2 pounds). The fetal surface is smooth, and shiny, traversed by branching fetal blood vessels, and attaches to the umbilical cord. The maternal side, covered by decidua basalis, appears rough, purplish-red, and raw. The placenta has a spongy interior, with villi forming an arborescent mass within the intervillous space. Maternal blood flows into the intervillous blood lake, providing nutrients for the fetus through the placental barrier.

As pregnancy progresses, the placental barrier becomes thinner, allowing the exchange of nutrients, water, salt, viruses, hormones, and other substances.

Uterine tubes

One of the two uterine tubes serves as the pathway for the mature ovum’s journey to the uterus. Male spermatozoa travel upward through the tube, where they encounter the ovum, leading to fertilization. In the initial days following fertilization, the zygote, or fertilized egg, descends within the tube towards the uterus. While situated in the tubal canal, the developing conceptus receives nourishment from secretions produced by the tube. Once the fertilized egg enters the uterus, the tube no longer plays a role in the pregnancy; its sole function occurs in the days surrounding conception. Throughout the progression of pregnancy, the tube gradually expands and accumulates more blood, a phenomenon observed in all pelvic organs. Some of its cells may exhibit a decidual reaction in response to pregnancy hormones. Concurrently, as the uterus enlarges, the tubes stretch upward, transforming into two significantly elongated strands on either side of the uterus.

Vagina

The initial pinkish-tan hue of the vaginal lining undergoes a bluish transformation in the early stages of pregnancy due to the dilation of blood vessels in the vaginal wall. As pregnancy progresses, the vaginal wall transitions to a purplish-red color, reflecting further engorgement of blood vessels. The cells within the vaginal mucosa increase in size, contributing to heightened vaginal fluid production as additional cells are shed from the mucosa’s surface. This process, accompanied by the thickening, softening, and relaxation of the vaginal lining and underlying tissues, enhances the distensibility and capacity of the vaginal cavity. These changes prepare the birth canal, facilitating the passage of the larger fetal mass.

External genital structures

External genital structures undergo similar modifications, softening, becoming more succulent, and turning extremely fragile due to increased blood and fluid accumulation. The purplish-red color persists in these tissues as a consequence of heightened blood supply. Darkening of the vulvar skin is commonly observed during pregnancy, particularly among women of Mediterranean ethnic groups.

Within the pelvis

blood vessels and lymph channels enlarge to accommodate the increased blood and tissue fluid volume in the uterus and other pelvic organs. Pelvic congestion and engorgement, both within and outside the uterus, are characteristic of pregnancy.

Changes in pelvic muscles, ligaments, and supporting tissues commence early in pregnancy, intensifying as gestation progresses. These changes are spurred by elevated hormonal levels in the mother’s blood during pregnancy. Adequate elasticity and strength in pelvic supporting tissues are crucial before labor, enabling the uterus to grow out of the pelvis while maintaining support. The muscles need to be soft and elastic during delivery to stretch apart without obstructing the baby’s birth. Softening and increased elasticity result from the growth of new tissue, as well as congestion and retained fluid within the tissues.

The bones forming the mother’s pelvis undergo minimal alterations during pregnancy. The joint between the pubic bones in front and the joints between the sacrum and the pelvis at the back may loosen in response to the hormone relaxin, produced by the ovary. While the impact of relaxin in humans is usually subtle, excessive relaxation can cause discomfort, backache, and difficulty walking, particularly near term. Pelvic joint relaxation persists post-delivery, contributing to postpartum backaches and discomfort.

Structural changes in the mother’s bones are minimal if her calcium reserve and intake are adequate. In cases of insufficient calcium, the fetus may draw excessive calcium from the mother’s bones, resulting in softening and deformation. This condition is rare but may occur in areas where extreme poverty and severe calcium deficiency prevail.

Breasts

The initial changes in the breasts during pregnancy mirror the commonly experienced premenstrual discomfort and fullness but in a more pronounced manner. This distinctive sensation serves as a specific indicator of pregnancy, often alerting women who have been pregnant before to their condition. Progressing through pregnancy, the breasts undergo enlargement, and the lightly pigmented area (areola) surrounding each nipple transitions from a flush or dusky color to a notably darker hue. In the later stages, the areola assumes a deep bronze or brownish-black shade, influenced by the woman’s natural pigmentation. Veins beneath the skin over the breast become more visible and enlarged, while the small oily or sebaceous glands (Montgomery’s glands) around the nipple become more prominent.

These transformations are attributed to significantly elevated levels of estrogen and progesterone in the woman’s bloodstream. These ovarian hormones not only induce these changes but also prime the breast tissue for the effects of prolactin, the lactogenic (milk-causing) hormone produced by the pituitary gland. In the latter part of Symptoms of Pregnancy, a milky fluid known as colostrum either exudes from the ducts or can be expressed.

After delivery, the pituitary gland is believed to release prolactin as a result of the decline in estrogen and progesterone levels. This release initiates the secretion of milk from the breasts. It is hypothesized that elevated hormonal levels inhibit the action or secretion of prolactin before delivery. As long as the mother breastfeeds her baby, prolactin continues to be produced, sustaining lactation.

Anatomic and physiologic changes in other organs and tissues

Cardiovascular and lymphatic systems

Throughout the Symptoms of Pregnancy, the increasing demands of the growing fetus and the mother’s tissues impose an additional workload on her heart. The heart’s performance is quantified by its cardiac output, measuring the amount of blood expelled per minute. A significant surge in cardiac output occurs between the 9th and 14th weeks of gestation. From the 28th to the 30th week, when the load is heaviest, a pregnant woman’s heart works 25 to 30 percent more than it did before Symptoms of Pregnancy. As the delivery approaches, the heart’s workload diminishes somewhat, reaching a load similar to the nonpregnant state after childbirth. This reduction in cardiac output and workload, despite the ongoing needs of the fetus and maternal tissues, is attributed to the more efficient manner in which tissues extract oxygen and nutrients from the mother’s blood during the terminal weeks of Symptoms of Pregnancy.

The position of the heart changes to varying degrees during pregnancy. As the uterus enlarges, it elevates the diaphragm, pushing the heart upward, leftward, and somewhat forward. In some instances, the large uterus may raise the heart to almost a right angle to the woman’s body near the end of gestation. These alterations, accompanied by some rotation of the heart, differ among individuals. Despite the greater workload, a healthy heart exhibits minimal or no enlargement even during the midportion of Symptoms of Pregnancy when the load is highest.

Changes in the heart’s position, increased workload, elevated blood volume per beat, reduced blood viscosity, and increased blood in the woman’s vessels may distort the sounds heard by physicians using a stethoscope. These functional murmurs, distinct from organic murmurs associated with heart disease, do not necessarily indicate a problem but may prompt referral to a cardiologist for evaluation. Symptoms of Pregnancy may induce minor changes in the electrocardiogram within normal limits.

Even women with serious heart disease, given proper care and without unexpected complications, typically navigate pregnancy and delivery successfully. Challenges may arise post-delivery when managing family-related stress.

Normal Symptoms of Pregnancy generally don’t elevate the mother’s blood pressure; in fact, a slight decrease is common. Any significant increase in blood pressure warrants attention from the physician, as it could signal the onset of preeclampsia.

During pregnancy, the pulse rate slightly quickens, reflecting the need for a faster heartbeat to accommodate the larger blood volume. Peripheral circulation acceleration contributes to elevated skin temperature, perspiration, and, in part, the redness of palms and dilated blood vessels in progressing pregnancies.

A notable circulatory change during pregnancy involves a slowing of blood flow in the lower extremities. This decrease leads to increased pressure in the veins, blood stagnation, and eventual swelling in the legs. These changes, exacerbated by the pressure of the uterus on pelvic blood vessels and hormonal increases, contribute to leg swelling and varicose veins in the lower legs, especially towards the end of Symptoms of Pregnancy.

Enlargement of lymphatic vessels in the pelvic region occurs in response to increased tissue fluid. As the uterus grows, it presses on these channels, impairing lymphatic drainage from the legs, resulting in swelling and distention of the feet and legs.

While some fluid retention in the feet, ankles, and legs is typical near delivery, sudden or significant swelling may indicate impending preeclampsia—a serious pregnancy disorder. Generalized swelling, affecting the hands, face, and other body parts, is a cause for serious concern.

Respiratory tract

One might anticipate that as the uterus expands and elevates the diaphragm, it would impede breathing; however, the lungs maintain their efficiency comparable to the nonpregnant state. This phenomenon arises from a modification in the chest cavity shape during pregnancy, where the chest diameter expands while its height diminishes, resulting in a slight augmentation of lung space.

The volume of air inhaled and exhaled by the lungs progressively increases throughout the Symptoms of Pregnancy. Shortly before delivery, the respiratory rate reaches approximately double the postpartum rate. This adjustment, akin to numerous other transformations in the mother’s body, represents an adaptation in a vital function crucial for providing escalating amounts of oxygen to her tissues and those of the developing fetus.

Gastrointestinal tract

Several modifications, sometimes causing varying degrees of discomfort, manifest in the physical condition and functions of the gastrointestinal tract during pregnancy.

Changes in taste and smell sensations, often prevalent in the early stages of gestation, are frequently accompanied by aversions to odors and a dislike for previously enjoyable foods. Complaints of mouth and gum inflammation among pregnant women are more likely attributed to inadequate oral hygiene, vitamin deficiencies, or anemia rather than the Symptoms of Pregnancy itself.

The stomach’s production of hydrochloric acid and pepsin, crucial for effective digestion, diminishes during pregnancy. This reduction in stomach acid may elucidate certain otherwise perplexing anemias that sporadically arise in an ostensibly normal pregnancy.

As Symptoms of Pregnancy advance, the stomach muscles experience a decrease in tone, becoming more lax, and the stomach’s contractility diminishes. Consequently, the time taken for the stomach to empty its contents into the intestinal tract prolongs. The upward displacement of the stomach during pregnancy, positioned like a lax pouch across the top of the uterus near term instead of its usual downward, semi-vertical orientation, combined with the diminished muscle tone and acidity, contributes to the regurgitation of intestinal contents back into the stomach.

These disruptions in gastric function play a role, at least in part, in the aversion to fatty foods, indigestion, upper abdominal discomfort, and heartburn commonly reported by pregnant women at various points during their pregnancies.

The muscular tone of not just the stomach but the entire intestinal tract diminishes. This results in slowed peristalsis, the coordinated, wavelike movements of the intestines, prolonging the transit time of food through the intestinal tract and causing a degree of stagnation in the intestinal contents.

Constipation and hemorrhoids, leading to rectal pain and bleeding, are prevalent concerns during pregnancy. Intestinal tract laxity and bowel content stagnation contribute to constipation. The pressure of the uterus on the lower bowel, inhibiting the gastrocolic reflex—a reflex stimulus from the stomach to the rectum—and the subsequent loss of the urge to defecate exacerbate constipation. Hemorrhoids, characterized by enlarged or varicose veins in the lower rectum, arise due to constipation, blood stagnation in pelvic veins, and pressure from the expanding uterus on pelvic blood vessels.

Liver

The liver, a vital organ involved in diverse processes such as metabolizing nutrients and vitamins and eliminating metabolic waste products, undergoes anatomical and functional changes during pregnancy. These adaptations are necessary to meet the increased demands imposed by the maternal organism, the expanding uterus, and, to a lesser extent, the developing fetus.

To address the heightened requirements of the mother’s tissues and the fetus, the liver enhances its capacity to synthesize proteins and supply minerals and nutrients. It adjusts to the elevated levels of hormones circulating in the mother’s blood during pregnancy. It aids in the disposal or detoxification of the greater amounts of waste material generated by the metabolic processes in the growing fetus, enlarging uterus, and maternal tissues. Additionally, the liver’s blood vessels enlarge to accommodate the increased volume of blood in the mother’s circulatory system, while simultaneously compensating for the higher number of circulating red blood cells.

In response to these demands, the liver experiences an increase in size and weight, and its blood vessels undergo enlargement. However, its overall anatomical structure undergoes relatively minimal changes during pregnancy.

The hormones produced by the placenta and the metabolic transformations occurring in the maternal organism, rather than those associated with the fetus, primarily contribute to the increased workload of the liver and the observed physical and functional alterations during gestation.

Urinary tract

The bladder and urethra change during pregnancy due to muscle relaxation, positional shifts, and pressure.

In early Symptoms of Pregnancy, the uterus presses on the bladder, causing frequent urination. As the uterus grows, it displaces the bladder upward, stretching and distorting the urethra. This leads to the thickening of the bladder wall, enlargement of blood vessels, and fluid accumulation, resulting in swelling, blood stasis, and mechanical inflammation.

Frequent urination diminishes in mid-pregnancy but recurs as the baby descends into the pelvis before delivery. The stretched muscles controlling urination become less efficient, causing stress incontinence—unintentional urine loss during activities like coughing or laughing.

Bladder changes near delivery, including swelling, inflammation, and blood stasis, increase susceptibility to bladder infections, marked by pain during urination. Distinguishing pre Symptoms of Pregnancy pregnancy-induced effects from infection requires urine analysis, and untreated infections can lead to serious urinary tract issues later.

Ureteral alterations occur in 80% of pregnancies, with increased size and dilation, especially on the right side, slowing urine flow. The kidney pelvis also dilates, losing tonicity. This stagnant urine in the ureters elevates the risk of severe bladder infections, involving the kidneys during pregnancy.

Post-delivery, the ureters promptly return to normal.

The kidney’s vital functions, such as selective filtration, secretion, and reabsorption, persist during pregnancy. However, the workload increases due to elevated water and blood volume and faster metabolism. Early Symptoms of Pregnancy cause dilute, less acidic urine with increased frequency, while later stages exhibit reduced urine output. Protein traces in urine, though occasional in healthy pregnant women, warrant attention, as larger amounts may signal preeclampsia or kidney disease.

Pregnancy lowers the kidney’s glucose reabsorption capacity, leading to transient glucose traces in urine. This emphasizes the importance of regular healthcare check-ups, including urine examinations, to monitor protein, sugar, pus, bacteria, and other abnormalities for a pregnant woman’s well-being.

Blood

The total blood volume in a pregnant woman’s body increases by approximately 25 percent by the time of delivery. This rise is attributed to an augmented blood plasma volume, resulting from fluid retention, and an increase in the overall number of red blood cells. The additional blood is necessary to fill the enlarged vessels of the uterus, transport oxygen and nutrients for the fetus and maternal tissues, and eliminate waste products. Moreover, it serves as a protective reserve in case of hemorrhage during delivery.

Throughout the Symptoms of Pregnancy, blood-forming organs like the bone marrow produce more erythrocytes (red blood cells) carrying iron and oxygen. However, despite the increase in production, a pregnant woman’s blood cell count usually declines. This count is measured as the number of red cells per cubic millimeter of blood. The decline occurs because the blood plasma volume rises by approximately 30 percent, whereas the total red blood cell count increases by only about 20 percent, leading to apparent anemia. These alterations lead to decreased blood viscosity, and the hematocrit, which gauges the relative proportions of liquid and solid components in the blood, is lower. A moderate increase in the number of white blood cells per cubic millimeter is common during early Symptoms of Pregnancy, but this increase diminishes in the later stages.

In the absence of other health issues and with sufficient available iron for hemoglobin production, a healthy pregnant woman’s red blood cell count typically remains above 3,750,000 cells per cubic millimeter, her hemoglobin above 13.5 grams per 100 cubic millimeters of blood, and her hematocrit above 35. (Normal values for nonpregnant women are 4,200,000–5,400,000 cells, 13.8–14.2 grams hemoglobin, and 37–47 hematocrit.) Physicians routinely conduct blood counts for pregnant patients every two months for regular assessment due to the necessity for repeated evaluation.

Endocrine system

Most of the endocrine glands undergo enlargement, and some experience functional changes during pregnancy; however, they return to a normal state after delivery.

The anterior lobe of the pituitary gland increases in size throughout the Symptoms of Pregnancy, yet the production of pituitary gonadotropins, which are hormones stimulating the gonads, ceases after the placenta starts producing chorionic gonadotropins. The pituitary continues to release hormones that stimulate other endocrine glands. Towards the end of Symptoms of Pregnancy, as the mother’s estrogen level decreases, the pituitary produces prolactin, a hormone that stimulates milk production. The posterior lobe of the pituitary gland remains unchanged in size or weight during pregnancy.

The thyroid gland undergoes moderate enlargement, but there is no actual increase in thyroid function during gestation. The parathyroid glands also increase in size during pregnancy, though their function is presumably unaffected.

The region of the pancreas responsible for insulin secretion, known as the islets of Langerhans, becomes larger. Any observed increase in function is likely a balanced response to the body’s demand for products related to carbohydrate metabolism. Plasma insulin or insulin-like substances in the plasma show higher levels during pregnancy, and the breakdown of insulin is also accelerated.

Levels of 17-hydroxycorticosteroids, hormones produced by the adrenal glands that influence protein, fat, and carbohydrate metabolism, increase in both blood and urine during pregnancy. However, their heightened levels are counteracted by an increase in transcortin, a protein that neutralizes their effects.

As Symptoms of Pregnancy advance, there is an increase in the secretion of aldosterone, an adrenal hormone involved in retaining salt and water in the body. This rise is thought to act as a protective mechanism, counterbalancing progesterone’s tendency to promote the excretion of sodium ions in the urine.

Skin

Pregnancy typically results in increased secretion from the oil and sweat glands in the skin, leading to more noticeable body odors. Changes may be observed, such as thinning and drying of hair, increased brittleness of nails, and the potential development of additional facial and body hair. Brunettes, in particular, may experience the “mask of pregnancy,” characterized by brownish pigment deposits on the forehead, cheeks, and nose. The skin may become puffy and thicker, giving the pregnant woman’s face a coarse and somewhat masculine appearance. Nearly universal is the increased pigmentation, especially around the nipples (areolas of the breasts) and the vulva.

During pregnancy, some women may experience bright red discoloration of the palms and the appearance of spiderweb-like red blood vessels on the skin of the arms or face. These changes are often linked to elevated levels of estrogen in the mother’s bloodstream. Fortunately, most of these alterations tend to resolve after childbirth.

The emergence of “stretch marks” on the breasts and abdomen during pregnancy is a result of elastic tissue tearing in the skin due to breast enlargement, abdominal distention, and subcutaneous fat deposition. These marks initially appear as pink or purplish-red lines during pregnancy but transform into permanent, scar-like marks after delivery. It’s important to note that the presence of stretch marks does not conclusively indicate that a woman has given birth, as they can also occur in women who haven’t experienced pregnancy.

Metabolic changes

Metabolic adjustments during pregnancy are essential for meeting the increased demands arising from the growth of breast and genital tissues, as well as the development of the conceptus (fetus and afterbirth). Additionally, reserves are established to accommodate the physiological demands of pregnancy, delivery, and the postdelivery period.

Basal Metabolic Rate:

The pregnant woman’s basal metabolic rate (BMR), indicating her metabolism at rest, is measured by the amount of oxygen consumed. This rate starts to rise in the third month of Symptoms of Pregnancy and may double the normal rate (+10 percent) by delivery. The increase is proportional to fetal size and reflects the combined effects of maternal and fetal activities. A rise of 20-25 percent in BMR is not indicative of an overactive thyroid gland.

Weight:

Early Symptoms of Pregnancy may witness moderate weight loss due to reduced appetite, nausea, and vomiting. Between the third and ninth months, women typically gain around 9 kilograms (20 pounds) or more. Ideally, weight gain should occur at a rate of about 0.5 kilograms (1 pound) per week, totaling 9 to 11.5 kilograms (20 to 25 pounds). Excessive weight gain, exceeding 11.5 kilograms, is a concern and may lead to complications.

Protein:

Nitrogen, derived from ingested protein, is crucial during pregnancy for fetal, placental, uterine, and maternal tissue growth. Adequate nitrogen intake is necessary for building reserves, and by term, approximately 500 grams (about 1.1 pounds) of nitrogen are acquired.

Carbohydrates:

Pregnancy affects blood sugar levels, leading to lower fasting blood sugar and prolonged elevation after glucose ingestion. Gestational diabetes may emerge due to increased insulin demands during pregnancy.

Fat:

Blood lipid levels, averaging 600 to 700 milligrams per hundred milliliters in nonpregnant women, increase to 900 to 1,000 milligrams during late pregnancy. This corresponds to the period when the fetus accumulates most of its adipose tissue.

Water:

Pregnancy involves increases in body water and total body fluid volume, with approximately 3,500 to 4,000 milliliters of additional fluid. This increase is distributed among the uterus, placenta, amniotic fluid, and fetus. Sodium retention, accompanied by positive chloride and potassium balances, contributes to fluid retention.

Minerals:

Adequate reserves and intake of iron and calcium are crucial for both the pregnant woman and the fetus. Serum copper levels increase during pregnancy, and sufficient phosphorus intake is necessary for the interdependent use of phosphorus and calcium.

Overall, understanding these metabolic changes is vital for ensuring the health and well-being of both the pregnant woman and the developing fetus.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signs_and_symptoms_of_pregnancy